Chemistry is heading towards computing. It's getting smaller and faster. High-throughput experiments (HTE) are part of this push. HTE draws on the experience of biologists and biochemists, introducing microplates and multichannel pipettes to miniaturize reactions, and robots to run these reactions quickly without sacrificing precision. But it's also been around for decades. So why are many in the field excited about HTE right now? Stereochemistry looks at the technological and cultural shifts behind current trends.

Subscribe to Stereo Chemistry now on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, or Spotify.

The following is the transcript of the podcast. The interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Matt Davenport:Welcome to Stereochemistry. I'm Matt Davenport, and today we're going to be talking about high-throughput experiments (HTE). HTE has been around for decades, but we hear a lot of talk about it now. So, in this episode, we're going to talk about why.

Before we get into that, though, I want to introduce my partner, colleague, and parent of young children, C&EN science reporter Sam Lemonick. Sam, how's it going?

Sam Lemonick: Hey, Matt. very good.

Matt: So I have a weird question for you. I just wanted to have a snack because I didn't want to starve during the recording session.

Sam: Clever.

Matt: I'm curious if you've ever had this happen to you, I don't know if it's a moral issue or if it's when I'm like, "We bought this food for our kids, but I want to eat it it"?

Sam: Yes, I do think about that and feel guilty. What helps me is realizing we buy him a lot of healthy stuff, like we have more fruit in the house now than we did before. And I should eat more fruits. That way I won't feel bad about eating his fruit.

Matt: [Laughter] Very cool. Well, I'm glad we had this conversation. That’s literally everything I need for my podcast, so I’ll let you go.

Sam: Okay. Thank you so much. Great to talk to you, Matt. real. It's a pleasure to be on the show.

Matt: But honestly, we're here to talk about HTE, specifically the area of ??synthetic organic chemistry, which we don't know much about to begin with.

Sam: Yes. You picked the wrong person.

Matt: I think that makes sense. I've heard that one of the reasons HTE is popular right now is because of its accessibility. I think we can test this hypothesis by asking two relatively unfamiliar science writers to talk about it.

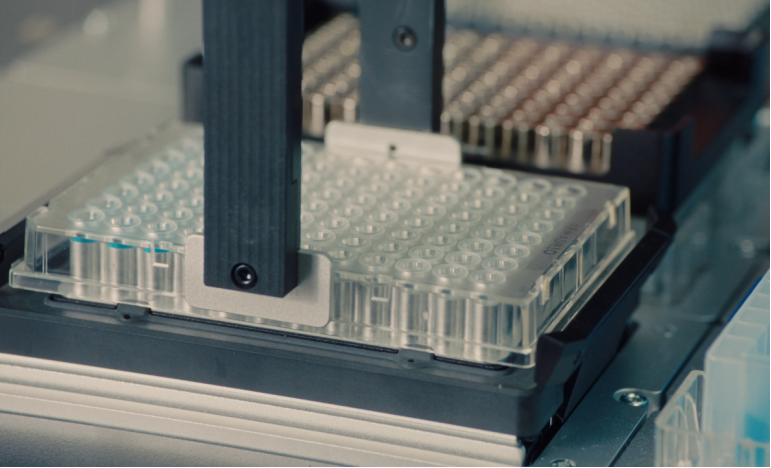

In fact, HTE itself is not difficult to understand. The idea is not to design one experiment to test one hypothesis in a beaker or flask, but to design many experiments to test multiple hypotheses in a multiwell plate or microplate. Therefore, these boards are most commonly made of plastic, and they are about the size of a pack of index cards. So they fit easily in your hand, and they have a lot of reservoirs or wells in them. They can be equipped with 6 holes, 24 holes, 96 holes. . .

Sam: Yeah, yeah. And they're going to get bigger, too, right? I mean, isn't there a well plate with over 1000 holes?

Matt: So I actually saw a 1,536-well plate when I was reporting, and I was like, "Those wells are so small. How do you get stuff in there?" The short answer is pipettes and /or robots, but I wanted to take a moment to explain this because I think there's a good chance that at least some people are thinking, "Wait. Haven't we been using orifice plates for a while?"

The answer is yes. But it feels like something special is happening right now. Let me take you back to when I first heard rumors about HTE.

Sam: Of course.

Matt: That was last August at the American Chemical Society national meeting in San Diego. As a reminder, ACS publishes C&EN, who produces this podcast.

I had the opportunity to sit down with a chemist from a pharmaceutical company and ask, which stories should I focus on? What is something you wanted to see in "C&EN" but didn't? They told me, “HTE.”

Now, fast forward to January and this tweet from Ash Jogalekar caught my attention. Ash is a well-known author of the science blog Curious Wave Functions and a professional chemist.

Ash Jogalekar:I started out as an organic chemist. My PhD is in organic chemistry. But I switched to computational chemistry. I always joke, and one of the motivating factors was when I damaged a $2,000 piece of equipment while working in the lab, and my advisor said, "Maybe you're not cut out for lab work. Maybe you should look into computing."

Matt: Ash now works for a company called Strateos, which is based in Silicon Valley. So it might not be surprising to hear that it's a tech company, but one that develops products like artificial intelligence and lab automation for biology and drug discovery. Ash is their Medicinal Chemistry Product Manager.

So I noticed this tweet from him that said: "I'm rarely a fan of new technology, but I'm willing to bet on Qualcomm using small volume and tablet-based chemistry to have a major impact on drugs and processes. Quantitative Experiments. "Chemistry in the Next Ten Years." "

Sam: I saw that tweet in January, too.

Matt: And you're not the only one doing this. For example, an organic chemist working at AstraZeneca responded to the tweet with, "We're taking it seriously."

Sam: My first reaction was actually surprise, because I thought, "Well, HTE is already here, right?"

Matt: Absolutely. I was discussing this via email with Mike McCoy, an editor on C&EN's business team. Mike has been covering HTE since its inception. Or the early 2000s. Or whatever we call it.

Anyway, Mike told me that he hasn't written about it in a while because it's pretty established in the industry and there are actually a few companies that specialize in HTE devices and services, such as Avantium, Unchained Labs, and Proper Named Hte, which celebrated its 20th anniversary last year.

To avoid confusion, from now on, whenever we say HTE, we will be talking about high-throughput experiments, not HTE companies.

Regardless, the question remains: Why is the field of HTE worth discussing now?

Sam: Yes, you know why? Do you have an answer?

Matt: Yes. The best answer I hear is that the field is at an inflection point. In other words, this podcast is a coming-of-age story. with robots.

In this episode, we discuss tools and techniques for HTE, including robotics. These tools are becoming easier to use, and they are getting better at performing more complex chemical reactions. Then there will be more chemists who are getting better and better at using these tools, trying to solve increasingly difficult problems, especially in process chemistry and medicinal chemistry.

So the confluence of these things happening right now also makes it feel like HTE has something special right now. Going back to Ash and his tweets, I wanted to check in on the feeling and ask, does it feel like HTE is having a moment?

Ash Chogalekar: Absolutely. I mean, I'm seeing a lot of interest in the literature and in the different companies that we've been talking to. This is really awesome.

Matt (interview): What is the most advanced technology in chemistry? You know, what's the difference between what you see in biology and what we see in chemistry?

Ash Jogalekar: I think that’s a great question. To be honest, this confuses me a bit too. Because it looks like biologists have been working on their version of HTE for at least 2 to 30 years, right? In fact, ironically, one of the reasons chemists are excited about this is precisely because they can repurpose many of the equipment, workflows, and techniques biologists use for HTE.

Matt (in studio): I want to follow up on this idea. For example, is HTE becoming more popular as tools and technologies in other areas, such as robotics and automated workflows, become more accessible? What Ash told me is that robotics and automation are driving this trend. But a cultural shift is also part of it.

Ash Jogalekar:Most HTE is done using sheets. It's plate-based, just like biologists do. In fact, that's a whole discussion in itself, if you look at the education of most chemists, synthetic organic chemists, you'd be hard-pressed to find a job as a synthetic organic chemist who had used plate chemistry in graduate school or postdoctoral work.

So I think it's just a matter of going from doing everything in beakers and vials and round-bottomed flasks for 150 years to doing everything in dishes. I think that in itself is a paradigm shift in thinking. That one too. Even now, this is uncommon. But it took a while for this idea to permeate the chemistry community.

Matt: So I think that's really a big thing that's happening right now, because of HTE, more chemists feel more empowered to explore more of the experimental space. As a result, more chemists entered the field and you were no longer restricted to doing only one experiment at a time.

Sam: This is how a lot of synthetic organic chemistry is done. I mean, even if you're talking about a 24-well plate, running 24 experiments at once is 24 times more than running one experiment at a time.

Matt: That really sets us up for this episode. We'll talk to chemists who have seen and felt these cultural and technological changes firsthand to learn how they got us to where we are today. But before we get into that, Sam, is there anything else you'd like to know right now to understand the situation?

Sam: Yes, we have discussed testing more hypotheses with HTE. But are there other big-picture reasons for people to be excited about this?

Matt: Absolutely. Ash has a very succinct way of summarizing it. So, yes, HTE allows you to test multiple ideas at the same time, and because you're running these tests in very small wells, you're using less material. This means HTE is cheaper and more environmentally friendly than traditional chemical methods.

Sam: It's kind of like bringing the smaller, faster, cheaper mentality that we see in technology into chemistry?

Matt: That’s right.

Ash Jogalekar:So I think ultimately the reason I'm so excited about this is that it allows chemistry to move in the same direction that computing and electronics did in the second half of the 20th century.

Sam: That makes sense. So, Matt, I do have one more baseline HTE question for you. What do good high-throughput experimental results look like?

Matt: I’m glad you asked that question. To answer this question, I’d like to introduce you to Melody Christensen.